You Don't Need to Code. You Need to Navigate.

I spent four years in the Navy not as a pilot, but as the person telling pilots where to go.

The E-2C Hawkeye is an unglamorous aircraft. No missiles. No guns. Just a massive radar dome bolted on top and a crew inside watching screens. While fighter pilots got the glory, we saw the whole picture. Tracked contacts. Coordinated assets. Made the calls.

The pilot flew the plane. We directed the fight.

Ten years later, I realized I'd been training for something that didn't exist yet.

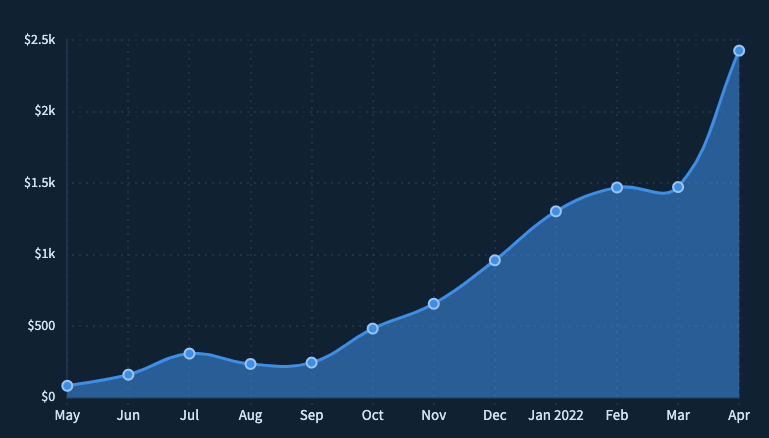

Recently I shipped features on two side projects and built a presentation automation tool for work. Something that would've taken months to spec and build. I still can't write production code.

What changed wasn't my technical skills—those remain bad. What changed was the feedback loop. The gap between having an idea and seeing it exist in the world collapsed from weeks to hours. Sometimes minutes.

The strange part? I don't understand most of what gets built. I can't read the code my tools produce. But I can read the output. I can see when something's wrong. I can steer.

I should be honest: the first few months were rough. I'd give vague instructions, get back something that looked right, ship it, and then watch it break in ways I couldn't diagnose. I once spent an entire weekend trying to fix an authentication bug that turned out to be a single missing environment variable. I didn't even know what an environment variable was.

But here's what I learned: the failures weren't random. They happened when I was lazy about constraints, when I assumed the agent understood context I hadn't given it, when I skipped the feedback loop because I was in a hurry. The failures taught me what the skill actually was.

Turns out, that skill matters now more than syntax ever did.

The Bottleneck Broke

The bottleneck that kept ideas trapped in non-technical heads just broke.

Three things converged at once:

Component libraries matured. The building blocks went production-grade. When the Lego bricks are that solid, assembling them becomes the easy part.

AI learned to wire things correctly. The boilerplate disappeared. The tedious glue work—state management, CSS alignment, all of it—tools handle that now. The gap from "design intent" to "working draft" used to be days. Now it's hours.

Platforms abstracted the hard parts. Authentication, databases, hosting, deployment—used to require specialized knowledge. Now they're checkboxes.

The result? If you can clearly express what you want, you can build it. Not because you understand how it works, but because you understand what you need and why.

Good prompting feels less like magic words and more like navigation.

You're not writing code. You're steering.

Everything I Needed to Know I Learned from StarCraft

Looking back, I'd been practicing this since I was eleven without knowing it.

Age of Empires. StarCraft. Command & Conquer. Total Annihilation. Warcraft (2 & 3).

In RTS games, you don't control every unit. You don't click each peasant to harvest each tree. You set rally points. You issue high-level commands. You manage resources and production. You scout the fog of war and make decisions with incomplete information.

You intervene when things go wrong—micromanage when you have to—but the goal is building systems that work without constant attention.

Great RTS players understand macro vs. micro. When to zoom out and think about economy and strategy. When to zoom in and control a critical engagement.

Working with AI agents is the same game. You're not typing code. You're issuing commands, managing context, setting constraints. You're building repeatable patterns that start every session consistently—build orders in RTS terms. You're scouting what the agent produces and intervening when it drifts.

I spent thousands of hours training for this in my parents' basement. I just didn't know it had a professional application. When I picked my Navy job, I chose the E-2C specifically because it felt like the real-world version of what I'd been doing since age eleven—watching the whole map, managing resources, calling the shots.

Three Builders Who Changed How I Think

I've been trying to understand who's actually succeeding in this new world. Not the hype—the people quietly shipping things that work. Three stood out.

Ben Tossel: The Practitioner

Ben shipped 50+ projects in four months. Used 3 billion tokens doing it. He can't read the code he produces, but he reads the agent output religiously.

— Ben Tossell (@bentossell) December 31, 2025

His workflow is deceptively simple: Feed context about what you're building. Switch into "spec mode" to pressure-test the plan. Question everything you don't understand. Then let the agent run while you watch and steer.

The part that stuck with me: "The fastest learning path is building ahead of my capability and treating bugs as checkpoints—fail forward."

He's not waiting to understand before he builds. He builds, hits problems, and learns from the gaps. The problems ARE the curriculum.

Sunil Pai: The Framework

Sunil applied Steven Johnson's "Where Good Ideas Come From" to agent work and landed on something useful: a map of where agents are strong and where they drift.

Agents handle incremental steps—the "adjacent possible." Small diffs from what already exists. Pattern completion. Fast iteration on defined problems.

What they're weak at: anything requiring reality to push back. They'll generate plausible nonsense all day unless you give them constraints, context, and feedback loops.

His core insight: what changed across the week wasn't the model — it was the user.

The agent didn't get smarter. The person using it got more explicit about what they wanted.

Angus Chang: The Business Model

Angus built Bank Statement Converter. It takes PDF bank statements and converts them to CSV. That's it. The whole product.

It makes over $20,000 per month in profit with minimal maintenance. He launched during the Web3 hype. It grew through the AI hype. He ignored both trends and kept solving a boring problem for accountants.

The lesson I took: boring problems + simple solutions + fair prices = sustainable business. You don't need to chase what's hot. You need to solve something real and charge for it.

But the reason it works isn't his technical skill. It's his product judgment: picking a boring problem, keeping it simple, charging fairly, saying no to enterprise clients who wanted to own his roadmap. The code is table stakes. The navigation is the differentiator.

These three aren't traditional engineers. They're a new class of builder. And the skill they share has nothing to do with syntax.

The Navigation Stack

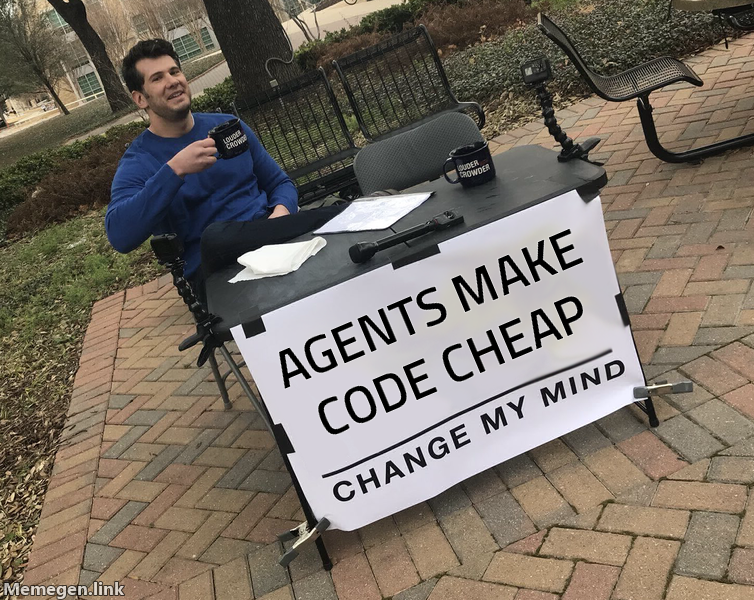

If agents make code cheap, what becomes expensive?

Sunil Pai's framework breaks it down:

![[navigation-stack.png]]

The formula: Constraints + Context + Oracle + Loop

Constraints aren't vibes. They're laws. What can't change? What breaks everything if the agent touches it? Write those down.

Context is what the agent needs to know about your world. Not generic best practices—your specific codebase, your conventions, your definition of "good." A portable instruction manual that follows you across projects.

Oracle means: how do you know when it's right? Not "looks good to me"—actual tests, benchmarks, something that creates a gradient toward truth. Hope is not a verification strategy.

Loop means small diffs, run checks, iterate. Not big-bang deployments. Tight feedback.

"Agents make code cheap," Sunil writes. "They don't make judgment cheap."

The scarce skill isn't typing. It's expressing constraints clearly. Designing oracles. Curating context. Running tight loops. Navigation.

What to Build: Simple, Lovable, Complete

Product people obsess over MVPs—Minimum Viable Products. Build small, ship fast, learn from customers.

The problem is most MVPs are too "M" and never actually "V." They're incomplete. Embarrassing. Customers don't want products that embarrass their creators.

Jason Cohen's alternative: SLC. Simple, Lovable, Complete.

Simple because complex things can't be built quickly, and you need to ship to learn.

Lovable because people have to WANT to use it. Products that do less but are loved beat products with more features that are disliked.

Complete because customers accept simple products but hate incomplete ones. v1 of something simple, not v0.1 of something broken.

Bank Statement Converter is the perfect SLC:

- Simple: One function. PDF in, CSV out.

- Lovable: Clean interface. Just works.

- Complete: Does the job on day one.

The pattern for the new technical class:

- Solve a problem you personally have

- Check if it applies to businesses (B2B beats B2C for revenue)

- Build the simplest complete version

- Make it lovable before feature-rich

- Charge fairly—and raise prices until the math stops working

Angus doubled his prices and made more money with fewer customers. Most people undercharge.

How to Start

If you're a PM, data leader, or analyst reading this and feeling the itch, here's where to start:

Pick one tool and go deep. Stop hopping between Cursor, Claude Code, Replit, v0. Pick one. Learn its patterns. The switching costs of tool-hopping exceed the benefits of the "best" tool.

Start with your own problems. Angus needed to track his spending. Ben needed internal tools. Your best ideas are already in your frustration list. What do you keep waiting for someone else to build?

Build your portable config. Create your version of agents.md or CLAUDE.md. Your preferences, your constraints, your definition of "good." Every session should start from your context, not zero.

Fail forward. Bugs are checkpoints, not failures. You don't study first and build later—you build and learn from the gaps. The problems are the curriculum.

Read the output, not the code. You're developing a new literacy. Watch what the agent does. Ask why when you don't understand. Close knowledge gaps as they appear. You won't become an engineer, but you'll become fluent enough to steer.

Ship complete before complex. One simple thing that works beats ten features that don't. SLC over MVP. If it's not lovable and complete, it's not ready—no matter how minimal.

Coordinator, Not Operator

In the Hawkeye, we had a saying: "The picture is the weapon."

It didn't matter how fast the fighters could fly or how many missiles they carried if nobody knew where to point them. The tactical picture—knowing where everything was, what it was doing, and what needed to happen next—that's what won fights.

The same is true now.

The AI is fast. It can write code I can't read. It can spin up features in minutes that would take engineering sprints. But it doesn't know where to point itself. It doesn't have the picture.

You do.

The question isn't "can you code?" It's "can you navigate?"

Can you see the whole battlespace? Can you express intent clearly? Can you set constraints that keep things on track? Can you intervene when things drift and let things run when they're working?

That's not engineering. That's command.

You've probably been training for it longer than you realize. Especially if you've been a PM or data leader. Coordinating stakeholders. Managing roadmaps. Understanding a domain deeply enough to know what should exist.

The tools finally caught up. The bottleneck broke.

What's the first thing you'd build if shipping was cheap?

You probably already know. It's the thing you've been waiting for someone else to build for you.

Stop waiting.